NEWPORT — People say it’s hard to make a living in Vermont, but it’s even harder to make a living in the Northeast Kingdom. The north country has always been the state’s economic stepchild, rich in natural resources but poor in population and almost everything else.

You have to be stubborn and determined to make your business thrive there. And general contractor Grant Spates, the owner of Spates Construction, Inc, is making it work, and on his own terms, too.

His company has done multi-million dollar construction deals, yet Spates has been known to work on a handshake.

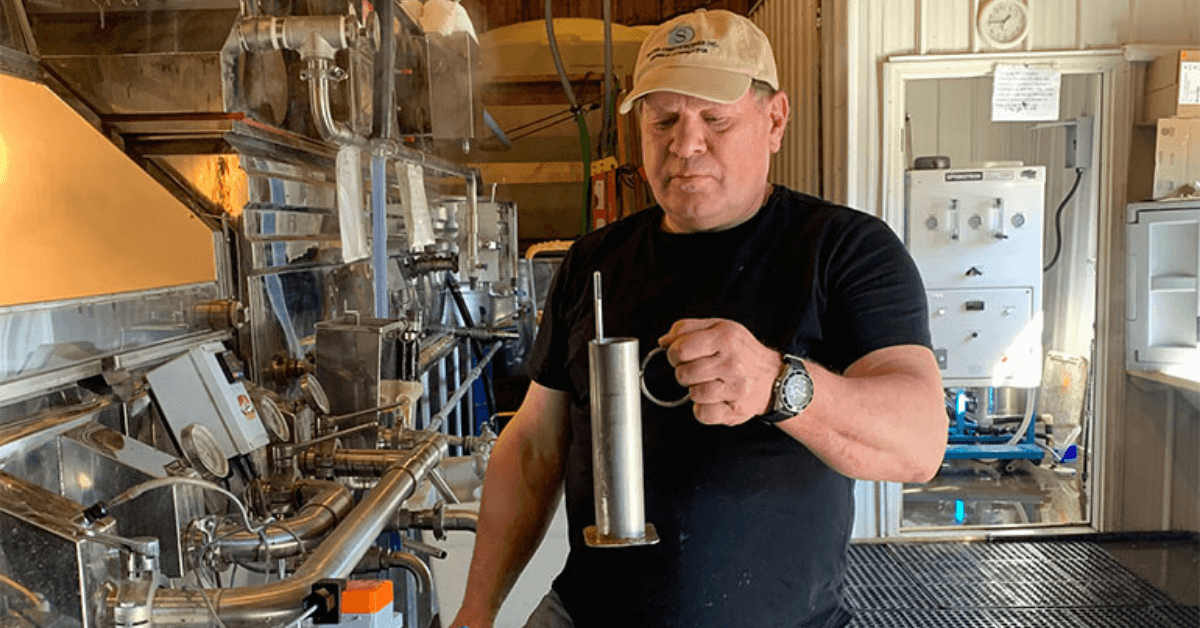

He’s an admitted long-time maple-sugaring addict who has turned his hobby into a thriving second business.

He’s designed his construction business so that his workers, some of whom have worked for him for decades, can have three-day weekends to hunt, fish and hang out with their families.

He’s been on almost every volunteer board in Newport and Derby.

He’s worried about the diminishing number of students going into the building trades, so he regularly donates his time to the North Country Career Center, trying to build young students’ interest in construction.

He’s outspoken, thoughtful and funny. Although every minute of his day seems to be spoken for, he’s having a lot of fun.

His is a true Vermont life.

Spate, 63, has lived almost his entire life in Vermont.

The company he now heads was founded by his father and mother in 1974; it specializes in commercial and industrial projects. It is a certified dealer of Star Buildings System’s pre-engineered steel buildings.

The company has done projects as large as the $7 million US Border Patrol Station and the $4.5 million Springfield State Office Building.

They have built more than a dozen schools, a courthouse in St Albans, a prison in St Johnsbury, housing such as Lakebridge in Newport, Hardwick Housing and the Bemis Block, along with many manufacturing and maintenance facilities across northern Vermont and in New Hampshire.

They have done two projects for the Vermont Economic Development Authority.

Spates did the VEDA projects with architect Tom Bachman of gbA Architecture and Planning in Montpelier.

“We’ve done three projects with Grant, and they’ve all been good,” Bachman said. “We did the Justin Morrill Visitors Center in Strafford, and the two projects for VEDA. It’s telling that VEDA would hire him twice. That’s a good indicator that he does good work. Our most recent experience was two years ago, at the Cross house. It was a complete foundation, new mechanical systems and a lot of electrical work, plus site grading and retaining walls. VEDA’s headquarters was the biggest project. It was the complete renovation of a four-story building, top to bottom, involving everything, including a new roof, new windows, completely new mechanical and electric systems, all new finishes, the addition of an elevator, major landscaping and redeveloping.”

Spates is a “very low-key kind of guy,” Bachman said, “but the company has done some impressive work in the state. He’s not a ‘Hey, look at me!’ kind of guy. He’s very honest. He’s fair. He treats the owner very well. He comes in with a fair price. I would say it’s a very honest operation, honest as can be. You get good value for your dollar.”

Spates and his two brothers took over the company when their parents retired.

After recently buying out his brothers, Spates now owns the whole operation. Even with the pandemic, the company did just under $6 million worth of business this year. It regularly employs 10 people, with part-time workers and subcontractors filling things out.

On occasion, Spates Construction jumps into New Hampshire.

“We do a little bit of work in Littleton, New Hampshire,” Spates said. “We did a garage over in Lebanon a few years ago. We did Lebanon Motor Toys, they were like a dealership for four-wheelers and things like that. So we get over there a little bit. But we don’t have an office or a satellite or anything over there. If there’s something that’s not too far, we can pop down to White River and get over into Lebanon pretty quick.”

When he’s not sugaring or building, Spates is chair of the Derby Select Board and chair of the North Country Career Center Regional Advisory Board. He also serves on the Career Center’s Building Trades Program Advisory Committee.

“Grant has always been there to support the North Country Career Center and our programs as well as the students,” said Eileen M Illuzzi, the career center’s director. “Each year at Christmas, Spates Construction makes financial donations for needy families and students which has, in turn, changed the holidays for many students. Grant is also very supportive of our college and career fair that we hold every fall. And he spends a great deal of time talking with students about their careers and passions. He is a firm believer in students pursuing their interests and passions and not just pigeonholing students into going to college if they aren’t interested in that option.”

One of his long-standing clients said he works with Spates on a handshake.

“We’ve done an awful lot of business on a handshake,” said Dave Marvin of Butternut Mountain Farm in Morrisville. “He’s always honored what he said he would do. He’s done seven fairly major construction projects for us. He built two warehouses, a warehouse addition and a large production facility. He revamped a derelict building we purchased for warehousing and shipping. He built a major addition to our sugar house. He actually re-roofed an old building up in the Northeast Kingdom. We keep going back for more.”

It should be noted that Spates sells his maple production to Butternut.

“It’s been a long, long-standing relationship,” Spates said. “Me selling syrup to them and them buying buildings from me. So I find myself feeling guilty, because the money kind of flows one way. So I stop at Christmas every year and shop at their Johnson store for my three daughters.”

He was laughing when he said that; obviously, his friendship with Marvin is strong, deep and playful.

Spates is “a true Vermonter,” Marvin said.

“It means that somebody, their word’s their bond,” Marvin said. “He also understands us because we’ve built our business a little at a time. We have to be frugal about what we do. His reputation is really good and we know of others who feel the same way we do. Grant is good people. I hope this doesn’t go to his head.”

Bob Currier, who manages the outside contractor sales at Poulin Lumber, has known Spates for decades.

“He is very, very community-oriented,” Currier said. “He is very active in lots of things. He took over his dad’s business and has done a very good job running it. He’s been very strong in believing in the trade schools and employing people who have come out of them. He’s developed a lot of young carpenters to be good employees of his. I sell to his business. He’s outgoing, conscientious, very smart at business and a hard worker.”

Currier was another person who said he didn’t want Spates to read what he says and get a swelled head.

“We always pick on each other,” he said, laughing.

Early Years

Spates was born in Newport; he’s the oldest of his three brothers; they also have an older sister.

Spates is only a first-generation Vermonter, but he sounds like he’s been here forever.

“My dad was born in Lynn, Massachusetts,” he said. “I’ve got some aunts and uncles that were born here in Newport. My grandfather had run a greenhouse. His brother-in-law was Al Richardson, who moved up here and was a photographer. They still have his old photos of the Newport area around here. And that’s what brought the family up here. Then my uncle Doug ran the greenhouse for quite a few years. So that’s the background on how we got up here.”

Spates’ father, a civil engineer, was the first in his family to go to college.

“My dad was teaching at Newport High,” Spates said. “But he’d also worked for Shell Oil. He got a call in 1963, and they offered him a regional district outside of Hartford, Connecticut. So we left Vermont. He was the project manager when they were putting up service stations in Connecticut and parts of Massachusetts. He did that from 1963 to 1970. And then we went back to Vermont.”

In Connecticut, Spates had two paper routes.

“I had the Hartford Courant in the morning and I had a local paper in the afternoon,” he said. “The Sunday paper was like a double paper and I couldn’t fit it in my bike rack. Dad would get up and drive me around Sunday mornings.”

During these drives, his father offered financial advice that stayed with him.

“I had a couple of people who owed me money,” Spates remembered. “And Dad said, ‘Go talk to them.’ He’s like, ‘Son, they owe you money. You can keep delivering their paper and then paying for it out of your pocket, or you can stop delivering their paper until they pay you.’ So I talked to them, and yes, they paid me. All those little things you did back then? They’ll help you down the road. All those kids who had paper routes or mowed lawns or shoveled roofs and all those little things you picked up, you put in your bag of things that helps you later on.”

In 1970, the family returned to the north country, settled down and bought a farm.

“We did some farming for a while,” Spates said. “We boys worked in the fields. And then my dad worked for Wright & Morrissey when they did the hospital in Newport.”

In 1974, Spate’s father bought a construction company called A. Joyal, Inc.

“And that’s when we finally did business as Spates Construction,” Spates said.

Both his parents worked in the company.

“My mom was in the office for years,” Spates said. “She retired a little earlier than Dad. He retired around 2001.”

All three boys joined the company as soon as they left high school.

“We went right into working with my dad,” Spates said. “I started in 1975 with him. And my other two brothers, after they graduated, started here as well. We all started as laborers and carpenters and worked our way up to running jobs. Eventually, I got pulled in the office for estimating and stuff like that — my dad turned that over to me. I learned that from him. I took drafting when I was at the career center.”

Spates must have been a handful at the career center, which is still a central part of his life.

“The drafting instructor at the time, they were tied more into (the metal manufacturing plant) Butterfield up here in Derby Line,” Spates said. “So it was tap and die, so it was reamers and tools. And I did that for about a year, which was good experience. And I’m like, ‘I want to draw houses.’ But they didn’t want to get any of those books for me. So I took the teacher’s plan book and hid it in the ceiling tiles. I left them a couple of notes on how to find it and quit the class.”

He moved to the career center’s agricultural program.

“It was actually good,” Spates said. “Harold Haynes was the instructor then; we have a Land Lab named after him up here in Derby. His ag class was great because we were farming at the time, but I also learned how to do my own taxes. We learned parliamentary procedure and things like that. That’s been useful, because I’ve been on the school board and chaired both the high school and junior high board. I chair the select board now right. So all that stuff was handy later on in life.”

Spates was on course to go to college, but maple syrup sidetracked him.

“I took all my courses to be able to go to college, and was enrolled in the career center as well,” Spates said. “And then my senior year, I rented a sugar bush with an option to buy. And we had 2,000 buckets. I got accepted to Vermont Technical College and the University of Vermont ag programs and then Dad was getting a construction business, and I had a chance to buy this sugarbush I’d rented. And so I didn’t go to school. I stayed here.”

His father gave him $1,000 for one year’s rent on the sugarbush and a down payment on the $30,000 Spates needed to buy the 40-acre property. He borrowed the rest.

“We put up a sugar house for about $5,500, and then we got into tubing in the next year because all my buddies, once they graduated, kind of left,” Spates said. “So we started putting up tubing in 1976. So I think I was in debt about $43,000 at about age 19. And I think I was making five bucks an hour from my dad.”

Spates eventually paid off the debt. He said he now has about 3,000 taps in Derby.

“And then my dad bought land in Newport Center, and about 10 years ago we set up almost 10,000 taps up there,” Spates said. “So we’re right around 13,000 between the two bushes. We bring all the sap to Derby and boil at one operation. I started with a toboggan and a copper tank and eight or nine buckets on some trees out here. And then I found an old two-by-four arch at the farm that Dad was working for Wright & Morrissey, who was building the North Country Hospital. And the tin knockers, put some new sides on, made me a pan and went from that. When people say it’s just a hobby, I say be careful. Hobbies can grow. And it’s not a cheap hobby, either.”

He learned from his mistakes with sugaring, Spates said.

“You’re always adapting,” he said. “You thought this layout of tubing might work in this section of the bush and then you found out it didn’t. Our old tubing methods, we put up just the one main line and then lines off of that. Then over the years, everyone found out that when you’re running vacuum up those lines, you’re really not getting vacuum to those trees, not once that mainline starts filling with sap. So we moved from that system to what they call a wet-dry system, where one line is your vacuum line and one line is the transfer line, and they manifold together. So the sugarbush tubing now is totally different than what it was when I started putting tubing up in, in 1976.”

When Spates’ parents decided to retire, they took assets out of the company and turned it over to their sons.

“And the office was right here, attached to their house,” Spates said. “So we had an agreement which worked out that we paid them rent, and things like that. And it was a good working relationship for both of them. They both passed away, but they were both able to stay right in the house here and not have to go into a nursing home.”

And Spates never did get around to going to college.

“Nope,” he said. “Didn’t seem to need it.”

Running the Business

Spates Construction has truly been a family business.

“So, at one point, I had two brothers-in-law and my father-in-law, my two brothers, my mother and my dad,” Spates said. “So yeah, it was a family business.”

Business has been consistent for the past two years.

“We’re doing probably just under $6 million worth of work, all commercial,” Spates said. “Once in a rare occasion we do something residential, but it’s usually for someone we know. Most of our jobs have architects involved. Or if we do the plans, we’re working with engineers and people we know for site design, Act 250 permits, etc. We’ve got a good group of people we’ve worked with to help us on a project. We could do some drafting. Oscar Thayer, who works in the office with me, has got a CAD (computer-aided design and drafting) program. But a lot of that design work we send out to structural and civil engineers.”

Being so far north presents its own set of problems. For one thing, his crews sometimes need to travel long distances. For another thing, Canada.

“When we did the Springfield office building, that was a two hour-plus haul for us,” Spates said. “So I tell people, most companies can put a map on a dartboard and draw a semicircle for their area of business. But when you’re up here, at the top of Vermont on I-91, we just have a big-ass parabola. We can’t go north. We’ve got the lake, you know, five miles of Memphremagog on this side, and you cross the border, and you look at all those big fancy houses, and you can’t do any work up there.”

Even before the pandemic closed the border, only specialized American workers were allowed to work in Canada.

“You’d have to be a real specialty trade,” Spates said.

Unions are a big reason that hiring Canadians to work in the US is no longer viable, even if the border were open.

“We used them in the company when I first went to work for my dad,” Spates said. “In the summers, we had a couple guys that were from Canada. That worked for a while, but right about after the 1976 Olympics, everything went big union up there. Before that, the wages were better on some construction projects down here. After that, you didn’t draw too many Canadians down here. We still have some that come down to do some granite work, some metal stud and drywall work, but they’re kind of independent and act as subcontractors. But the wages are better up north. So you don’t pull too many people down into Vermont. Like I said, unless you’re a super, super specialty contractor. You know, even if I had a relative up there, I probably couldn’t go put his mailbox back up after it got knocked down with a snowplow.”

Spates does not see the need for unions now.

“I think there was a time and place for unions in this country,” he said. “Back when working conditions were really bad, and wages were really bad. But I’m still kind of an open market type of guy. You know, when we do a state job you’ve got different wages. When you do a federal job, you get different wages. And I think we could do a lot more projects with that same money if it was just an open market.”

A lot of Vermont mills have closed over the years, so lumber has become an industry that flourishes across the border.

“You see the logs go north, they get sawed and then they come back down,” Spates said. “Most of the lumber we buy is still through Poulin’s, or Sticks and Stuff, or something like that. A lot of lumber comes out of Canada, but we’re not buying too much directly from Canadian vendors. It’s been that way for quite a while.”

Closing the border for COVID didn’t affect Spates’ business very much; economics did.

“We do steel buildings, and steel’s gone up,” Spates said. “I think as you get more people vaccinated and production comes back up, I think you’ll see those numbers stabilized. But right now, you know, the market for steel and lumber are pretty volatile. Which makes bidding fun, right?”

Star Manufacturing has plants throughout the US, so pre-engineered steel buildings are always available.

“We do a lot of them,” Spates said. “A lot of your commercial buildings are steel buildings. As you start getting into bigger footprints, you’re going to be metal stud, you’re going to be structural steel block, or you’re going to be pre-engineered buildings. The codes limit how big you can go on wooden buildings. So as you start phasing out of wood-frame buildings, as you get into bigger commercial projects, you go to steel.”

COVID has affected his business, Spates said.

“We were doing a renovation on an elderly housing project here in Newport,” he said. “They were giving us two units at a time. They were moving the tenants out completely while we completely gutted the two units. And then, when COVID hit, we were still adjacent to two occupied units. Those we had to get shut down completely. And we were about to start work at the Sheldon school. Actually, we were able to get over there earlier. Initially, we weren’t going to be able to get over there until school was out, of course. But as you know, once March hit a year ago, things changed with schools. So actually, we’re able to get over there a little earlier than anticipated, which worked out because we weren’t dealing with kids and staff. We still have some siding work to do this fall. But the inside work we were doing was done.”

Construction was one of the first industries to thrive during COVID, mainly because much of it is done outside.

“We were able to put protocols in place,” Spates said. “And we did the same things on the site with subcontractors and temperatures. We kept smaller crews and were allowed to build up. First, just a couple of guys could work in close proximity to each other. And then, as the governor opened it up, we could put on more. But you could just put a network of smaller crews out there and keep them away from each other. I think overall, we’re probably one of the easier industries because a lot of the work is outside, or we haven’t totally closed in the building yet.”

The renovation market became tougher; most contractors didn’t want to work inside homes.

“But I think you saw that a lot of people were home, and were saying, ‘I can work on that. I’ve got time,’” Spates said.

Now that vaccines are available, Spates is waiting for new business to start up.

“We’re slow right now,” he said. “But we’re waiting on a metal building to come in, and we’ve got some foundations to get going on once the weather breaks. And we’re bidding a bunch of stuff. Interest rates are still not bad. But until things really get up and running, everyone is kind of feeling out the market to see where things are going to go. I think it’s a lot more positive out there now than a year ago, and everyone’s wondering ‘What’s going to happen and ‘How’s it going to impact me?’ But I think as far as the market, once you get production back up, mills open back up, and plants open back up, you’ll see a stabilization.”

Workforce

Spates tries to make life easy for his workforce. For one thing, he doesn’t like to take jobs that are too far away from home.

“We try to stay to under two hours,” Spates said. “An hour and a half is good. You start with two hours, those become longer days.”

But business is business, so Spates has a new way of looking at jobs

“When we take jobs that are further away, we try to do a four-day workweek for 10-hour days,” Spates said. “You know, give people a three-day weekend. Which, if you live up here, most of our guys, they’re outdoors people. So they don’t mind three-day weekends for fishing, hunting, or doing their other stuff. We’ve always tried not to do much overtime on the weekend, just for that same reason. Everyone needs some time for themselves and their family and what they want to get done at home. So we’ve never been ‘Let’s make sure we’re working every Saturday.’ We kind of took the opposite philosophy of mostly leaving weekends alone unless we absolutely need a Saturday for something.”

Spates said he learned this the hard way. Like I said, we used to travel more,” he said. “But travel is tough on the crews and on families. Especially if you’re traveling out of town a lot. I know I missed a lot of my kids’ life when I was running jobs. When my daughters were seniors, I made sure I went to every one of their sporting events and dance events, and everything else I had missed out on when I was in the field running jobs. You learn from that.”

Spates’ employees — some of whom joined the company when they got out of high school — are now getting older. He has learned to accommodate them.

“We did our own concrete for quite a few years,” he said. “And that’s tough work. As the guys got older, that was something we phased out. You get smarter as you get older. As the workforce gets older, we’ve invested more in man lifts. So things we probably used to do more, like going up and down ladders, now we don’t do more. We’re dealing with an aging industry of guys. If you want to keep them around longer, you’d better invest in equipment and ways to move material and make it easier on them.”

This goes along with Spates’ philosophy of three-day weekends.

“For some people that just get out of school, and want to make a ton of money, they work a ton of overtime, then we may not be the right match,” Spates said. “But I think for those that want to have a family, have time to do things with their family, have weekends for themselves, I think it’s been a decent philosophy for those who have stuck with us.”

Dwindling Population

Spates has no interest in growing his company; finding new workers is a big reason why.

“If you look at the trucking industry, the construction industry, the manufacturing industry — all of us are competing for that same individual,” Spates said. “In all three industries, the average age of workers is in the late 50s. People are retiring, and you’re not backfilling with enough individuals. So I can’t see myself saying I want to get bigger at this point in my life. We used to do concrete work, for example. Now we’ve subbed more and more of that out. But if we kick that can down the road to a subcontractor, they’re in that same mode now of finding enough individuals to replace those who have retired. So it doesn’t look good for a company that wants to expand. There’s just not enough people in the trades industries.”

This is especially true in the population-thin north. Spates pointed out that North Country Regional High School has gone from around 1,200 students in grades 9-12 down to below 725 now.

“At the career center, we still keep a good percentage of juniors and seniors,” Spates said. “But our numbers are down. At one time, our building trades class was big enough to have two instructors. Now we don’t have the numbers.”

Spates said one difficulty in finding students slated for the building trades is the changing nature of teenagers.

“Kids don’t mow lawns anymore,” he said. “They don’t do paper routes. They don’t shovel roofs. Take farming. When I grew up, with a lot of the high school kids I knew, if they weren’t living on a farm, they were working for friends of theirs on a farm. Now you’ve modernized farming. It’s a tough market. The farm kid thing, you knew how to weld. You knew how to fix stuff. They were MacGyvering 24/7 on the farm, right? Those were the kids that want to work the heavy equipment because they’ve been on a tractor since they were 12. Those are the kids everyone wants in the trades. They knew how to work hard. They were smart. They could figure stuff out. As you lose that agricultural base, and lose those kids, you lose workers as well.”

To meet the challenge, the career center has added courses in working heavy equipment and in natural resources for students who are interested in logging and sugaring.

“But you’re not having as many kids born as there were,” Spates said. “So it’s a numbers challenge all the time. You’re trying to recruit as many kids as you can into the different programs, but you’re also dealing with numbers that are a lot lower than what they used to be.”

Jay Peak

Like a lot of people, Spates was excited about Jay Peak’s plan to develop the region through the EB-5 program — foreigners invest $500,000 in a project that creates jobs and get a green card in return. He did two projects at Jay Peak and was negatively impacted when developers stole the investment money and the whole scandalous scheme blew up.

He’s sorry it went “to hell in a handbasket,” because big infrastructure jobs are hard to come by in the north country.

“We had the framing of two of the condos at Jay Peak,” he said. “We had 15 people on payroll and I was subcontracting another 15. So we basically had a payroll of 30 people. And it took us like almost 90 days to get paid. And it’s too bad. That was a lot of infrastructure that got built.”

Spates said he would like to see state government put money back into that area.

“They’re both up for sale,” he said. “I think Jay Peak will sell before Burke. But Newport still has an issue with the hole in the ground where those buildings were torn down. I would like to see the state step up. They had the fiscal oversight. It was fine for those of us on the outside to be cheerleaders. But the state had the regional fiscal oversight for the EB-5 program. And I think there were some canaries in the coal mine that they didn’t listen to early on. I think if they’d had, they might have caught on what was going on quicker.”

Who were the canaries?

“If you track the history of what went on up there, you know that with the EB-5 program, there was no guarantee of you getting your money back,” Spates said. “But these investors were told they would. I think some of the first ones who were on the first hotel project, all of a sudden found they weren’t on the ownership list. The paperwork was changed, and they wondered why. They were the ones that finally hired attorneys and dug deeper into what was going on, which started bringing light to the whole thing.”

Spates still thinks the EB-5 program was a good idea.

“It’s too bad it all went to hell, because the EB-5 program, you know, was a good program,” Spates said. “You’ve got people from out of the country who want to invest in the country to be able to move their family here. They want to maybe start a satellite company over here, or bring jobs over here as they move the company over here. So it was kind of a good program, especially in a rural area.”

The Future

Spates has now finished buying out his younger brothers; both left for health as well as financial reasons. He and his ex-wife have three adult daughters, and none of them are interested in being the third generation to run Spates Construction.

“I had one daughter who did some drafting when she was in high school, but then she joined the Navy her senior year,” he said. “She did nine years in the Navy, then went out to the West Coast, got a chopper license and now she fights fires. I don’t see us getting so big that there’s a corporate chopper in our future, and I liked it better when she was just doing the wine tours in California. But she was the only one who might have been interested in the company.”

Another daughter is based in Massachusetts and works for a Canadian-based insurance company; the third lives in Maine and works with foreign students.

Spates thinks the future, for him and his partner, Carol Brown, lies in sugaring.

“We’re working on looking to do more with the maple,” Spates said. “We’re going to open a website. I think we’re going to buy some bourbon barrels from a Vermont distillery and try our hand at some of the maple bourbon specialty syrup. See where that goes. So you know, you’re always gonna be trying something, right?”

Selling the company isn’t something Spates likes to think about.

“I’ve still got my health,” he said. “I keep telling people, ‘I’ll keep doing this as long as it’s fun.’ How do you define fun? Every day has its challenges.”

He likes fishing in the summer and skiing in the winter, but COVID put a damper on skiing this year.

“We’ve got a camp on Lake Willoughby and I enjoy fishing there,” he said. “I’ve got a 1934 Chris-Craft boat that I like putzing around in on the lake on a nice calm day. I didn’t ski this year. I like skiing with my daughters or my grandson. But skiing has been different for everyone this year. So I just stayed away from the ski areas this year. I like to do it with my kids when they come up, and there wasn’t much of that happening this year.”

Coming out of the pandemic, Spates said he is hopeful for the future of his industry.

“You look at the equipment and how it’s going to change,” he said. “There’s some things in industry that can be modularized and built inside. But as I tell kids, you’re never gonna outsource everything you do in the construction industry. I can’t tell you where the windows and doors and stuff will come from in 20 years. But you’re still going to need boots on the ground. You’re still going to need men and women in hard hats, installing, right? You’re not going to outsource that totally. Fast forward 100 years from now, robots are probably doing what we’re doing. That’s gonna happen probably quicker than we think.”

Spates is nothing if not industrious.

“You got to keep busy,” he said. “For example, we always did firewood. We split most of it by hand when we sugared. Then my brother built a four-foot splitter years ago, and I bought a wood processor to do firewood. So we were using that for sugar wood. Then when we added these other taps, I told my brothers, ‘I’ve been doing firewood since I was 17. I think I’m going to switch over to oil for the boiling.’ It’s easier if I need to be in the office to do something, or we if got a bid we’re working on. It’s a lot more convenient for me. But we still sell firewood, and I bought a bandsaw mill a couple years ago. So that’s on my list of things to play with when I retire, which I have no idea when that’s going to be. We’re still having fun. So I say, keep doing what you’re having fun with.”

This story first appeared in Vermont Business Magazine, written by Joyce Marcel. Joyce is a journalist in southern Vermont. In 2017 she was named the best business magazine profile writer in the country by the Alliance of Area Business Publications. She is married to Randy Holhut, the news editor/acting operations manager of The Commons, a weekly newspaper in Brattleboro.