By Susan Davis

NEWPORT — Conservationists are raising the alarm about a 60-year-old oil pipeline running through the heart of the Northeast Kingdom, and the thick, “peanut butter,” highly corrosive and chemically treated sludge called tar sands that could be pumped through it.

About 25 people gathered at the Hebard Building Tuesday night for a panel discussion hosted by the Memphremagog Watershed Association (MWA) and the National Wildlife Federation.

The watershed encompasses about 700 square miles of waterways and wetlands throughout Orleans and Essex County, including the Missisquoi, Barton, Upper Connecticut, Passumpsic, Clyde, Lamoille and Black rivers, over 20 lakes, and about a dozen municipalities and gores.

Although about 75 percent of Lake Memphremagog is in Canada, about 75 percent of the waters flowing into the lake come from this watershed, so any threat to the watershed is a direct threat to the lake, explained Don Hendrich, a former North Country High School teacher and member of the MWA board. A threat to the lake is a threat to the economic viability of the Northeast Kingdom, he stated, since this area relies so heavily on tourism dollars.

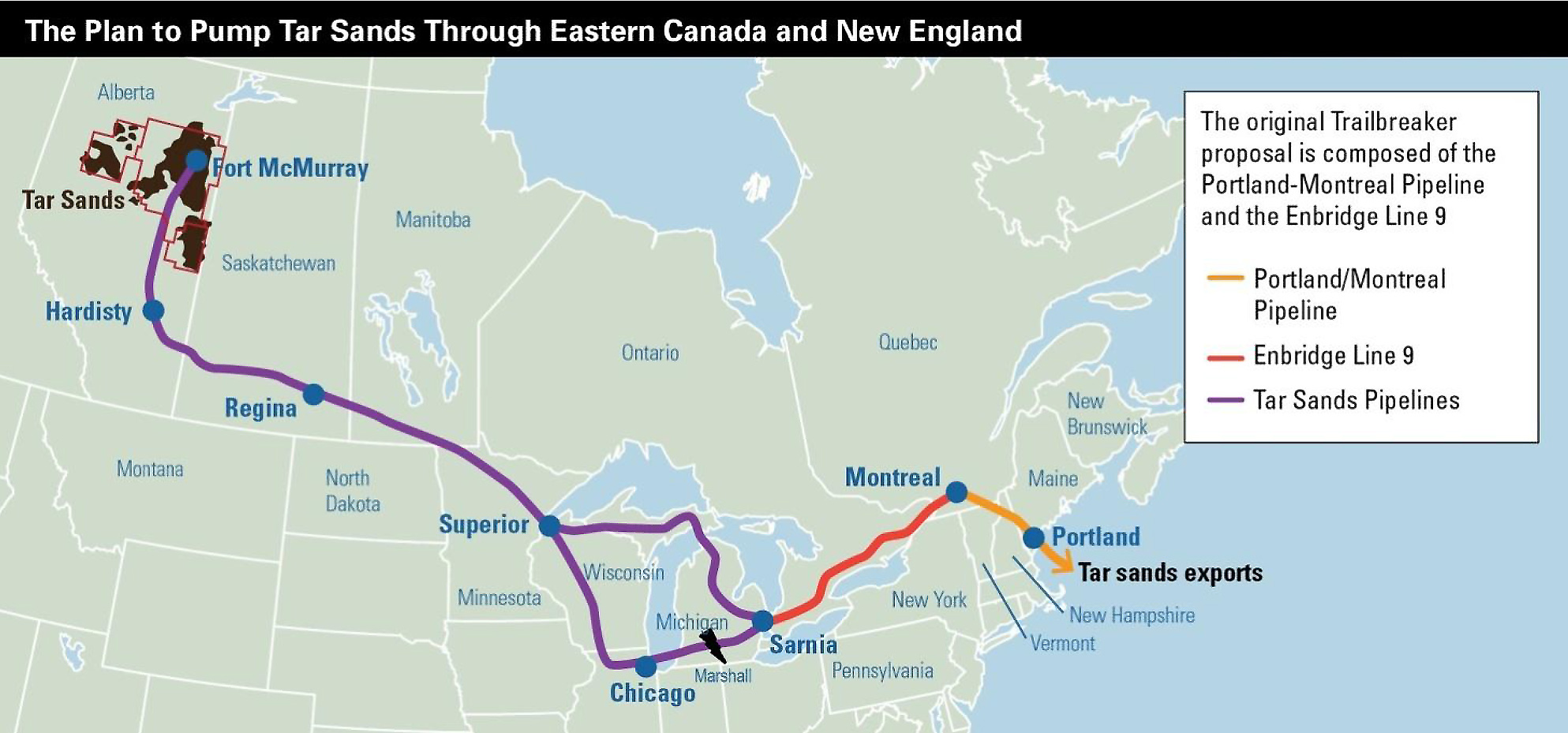

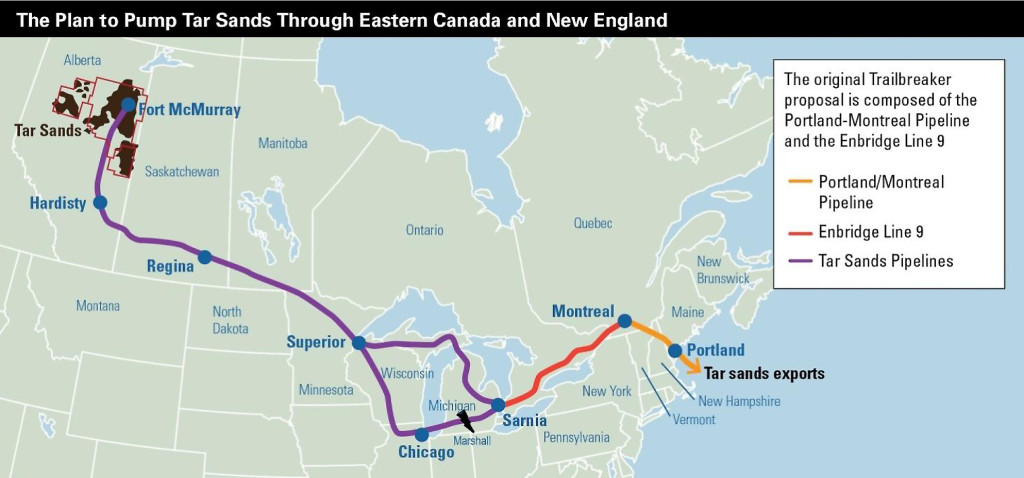

Panelist Annie Mackin, of the Vermont Tar Sands Project, National Wildlife Federation, said the existing pipeline runs from Portland, Maine, to Montreal, through North Troy, Irasburg, Orleans, Sutton, Burke and Victory Bog. Various stretches of the pipeline were built in 1940, 1950 and 1960 and reportedly have a lifespan of 60 years.

Two things make tar sands particularly dangerous to the watershed, Mackin explained: the thick, goopy, tar quality of the oil itself, which sinks to the floor of waterways during a rupture of the line; and the chemicals, used to make the tar sands fluid enough to run through the pipe, which contain high amounts of toxic metals and carcinogens that have been linked to everything from birth defects to emphysema to cancer.

Tar sands spills in Kalamazoo, Mich. (July 2010), and Mayflower, Ark. (March 2013), demonstrate the potentially damaging impact of an oil spill in the Northeast Kingdom, Mackin said.

Mackin and Hendrich were joined by David Stember, U.S. National Organizer of the environmental group 350.org, and by Greg MacDonald, a member of the board of directors of Sierra Club Vermont. Panelists discussed the history of the pipeline; the political battle in South Portland, Maine, around a controversial waterfront protection ordinance that would bar expansion of petroleum facilities that could handle tar sands; past breakdowns of the pipe; and the large investment and momentum behind the push to complete the pipeline.

Stember also spoke about his trip to the tar sands oil fields of Alberta, Canada and the devastation being done to the boreal forest there. That forest is “one of the Earth’s lungs,” he explained.

In February of 2013, Larry Wilson, CEO of the Portland Pipe Line Corp., told the Vermont Legislature’s House Fish and Wildlife Committee that there are no current plans to pump tar sands through the pipeline, but the company is opposing any legislation to prohibit such a move.

Tuesday’s panelists stated that actions speak louder than words. Tar sands oil has already reached Montreal, said Mackin, and the South Portland ordinance comes to a vote Monday, July 21.

“The industry is talking out of both sides of its mouth,” MacDonald said.